|

As Grant noted on the exposure sheet, October 28, 1984 was

the first day of shooting on the sets. It was a scene on the bridge following the accident in the transporter room where Science

Officer Bill was misassembled into a large blob of clay. It was a relatively uncomplicated scene with Klurk seated in his

chair being questioned by Mr. Pastafazoola sitting at the navigator's console. We discovered, as shooting progressed, that

certain color clay was more durable during scenes where the characters had to stand a lot. Blue worked well for this while

yellow clay would begin to sag and fall over. Most of the crew-persons in yellow uniforms spent much of the film seated

or propped behind consoles.

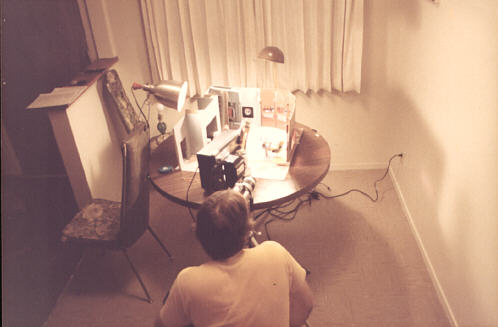

| Art shooting on table before going to counter top. |

|

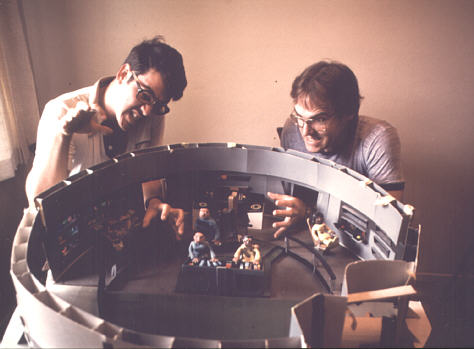

During our animation tests, Grant and I realized that my original method of shooting

two frames of film for each movement wouldn't be smooth enough now. We shot a scene on twos and again using only one frame

per movement. The fluidity of the action justified the work and every animated scene in the film was done on ones. Since the

dialogue was already mapped out on the exposure sheets, this didn't seem like it was much more laborious than doing it on

twos.

Grant worked out a frame counting system (he ran the camera's shutter release cable

while I hovered over the sets doing the character movement) using a calculator. He punched in the total number of frames for

a particular piece of dialogue and then hit minus one after the first frame was exposed. As the scene progressed, Grant would

press the minus symbol to register another frame done. When the calculator reached zero, the line was shot. I might add a

bit of business before and after the line to give myself cutting room during the editing phase.

| Grant and Art give the bridge crew a hand. |

|

We finished the bridge scenes around Christmas time of 1984.

There were a few retakes but by January 5, 1985 we moved on to Space Station Kmart. After the marathon on the bridge,

these shorter sequences seemed to whiz by. Also, by then, we had developed a smooth working arrangement that helped us maximize

our shooting output. For the filming of the travel pod interior with Klurk and Scotch approaching

the ship, we went through a 50 foot roll of Kodachrome in one day at one frame per movement. That's approximately 3600

frames.

Since I was trying to do this project as professionally as possible, I went

to the expense of having sound-striped workprints made from the camera original. This was to minimize the need to run

the original through any machinery and avoid scratching it. The workprint was edited and projected with rough sound added

to it. Unfortunately, the projector was finicky about the splices and would flicker on some and behave on others. I avoided

projecting the print very much as well, which would cause a problem later. Without viewing the entire film in progress,

I failed to detect the slow spots that would bog down the momentum. The second half of the story takes place mostly on

the bridge and got a bit monotonous. Some pre-emptive editing might have solved this beforehand.

As we drew closer to finishing photography

on the sets, Grant began readying the models for the effects portion of the film. The fluorescent tubes used in the engine

room were placed inside the Fulton's Folly model. We assembled other ships for the Martian Rush Hour sequence, even

some non-Star Trek ones. There were a couple that were reconstructed pieces from the first starship models Grant attempted

to illuminate. With his enlistment finishing up in July of 1985, the pressure to complete the project was on.

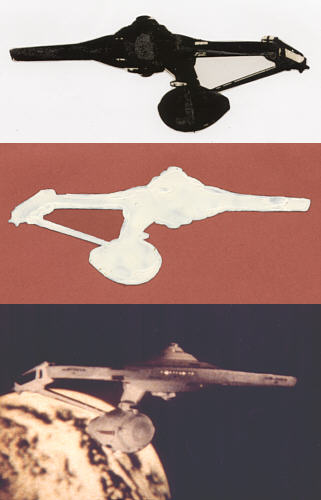

| The "live" ship in space. |

|

At first, Grant wanted to shoot the starship model "live"

against a starfield instead of my multiple projection method. We made a number of tries but ran into a focus problem keeping

the model and rear-projected slides sharp. There was also the matter of hiding the post that supported the ship. One dim scene

from the tests did make it into the final film but we reverted to the projection method to achieve the rest of the effects.

When we committed to the projection method, the scenes were broken down in layers,

much as people use Photoshop today. If there was a moving element, like a ship approaching, it was shot on Super-8 against

a black background the way I did the original STAR TRIX in the 1970's. If it passed behind a planet, the CAPT. COORS method

of cut-out masks was used. The planet was front-projected against a white circular paper cut-out and the moving ship was rear-projected

so it appeared to go behind it. If the model needed to remain static with something happening outside it, slides of the ship

were front projected.

| Top: Litho from slide. Middle: Painted on reverse. |

|

| Bottom: Completed composite. |

Grant devised a way of making the masks for the ship more precise by copying the

slide on lithographic film, then painting white over the image. Since the mask was made from the exact slide, we could line

it up evenly on the screen. This system worked so well it was applied to other scenes we didn't think we'd try earlier in

the project. As shown at left, the model was the static element with the starship slide front-projected. I photographed a

slide of the earth receding in the background on Super-8 movie film and rear-projected it on the screen behind the ship slide.

The screen was a large sheet of fine grain tracing vellum.

| Art with Elmo projector doing a rear-screen image. |

|

At the risk of being a spoiler, I'll need to give away a major

story point to explain one of the effects. After much fumbling around inside the mysterious gigantic spacecraft, Klurk and

crew discover an old, charred starship. The alien probe takes the form of Ineedya and whisks the Captain, Specks, Heckler

and Dr. Magillacuddy outside for a closer look. An atmosphere is provided for them as they gradually discover the truth. The

derelict ship is the original Fulton's Folly that was thought to be destroyed in the final STAR TRIX short.

| When starships collide. Grant holds the old ship. |

|

These scenes were animated against a large rear-projection slide of the saucer

of both ships. A scene showing a glowing red and blue platform hovering between the two large vessels showed where our heroes

were in relation to the ships. Grant used his airbrush markers to give the old Fulton's Folly a number of burned areas on

the hull. He also rigged up the warp engine caps to glow to life near the end. When rummaging through my photos and exposure

sheets, I found the comic strip style story for the film and discovered that I had originally written a different ending than

what was shot. The first version had the Captain and his party survive except for Heckler and Ineedya. There's a final sequence

where Mr. Scotch misinterprets Klurk ordering a saucer separation. The last shot of the film has the saucer wafting away from

the engineering section with Klurk berating Scotch as they go. STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION finally got around to showing a

saucer separation in the 1987 pilot.

In another case of parallel development, a scene in the 1999 feature film GALAXY

QUEST shows the actors-turned-spacemen piloting a real starship out of drydock. The helmsman steers a bit too close to the

edge of the structure causing a hideous scraping sound. In 1985, the Fulton's Folly II also makes a rough departure from drydock,

clanging against the sides as it goes. We had to build the cage-like facility from scratch using plastic strawberry containers

as raw material. It was a very flimsy item, held together with a plywood ceiling that had various bits of detailing added

to it as well as small lights. A sign was added to the side reading Khan's Body Shop, a nod to STAR TREK II: THE WRATH OF

KHAN.

| Art and float from 1985 Lompoc Flower Festival. |

|

On Saturday, June 25, 1985 I was waiting for Grant to arrive to start the day's

shooting on the optical effects. When he did show up, he insisted I come outside to see something. It was the weekend of the

annual Lompoc Flower Festival and the floats for the parade were lined up around the corner. I've never been much for parades

so I balked at coming along. Grant insisted that there was something I HAD to see. When we came around the corner to H Street,

there it was! A large, flower bedecked replica of the Enterprise ready to travel the parade route. We rushed back to the apartment

to get my Polaroid camera and took several shots of it before it was driven away.

By July 1985, the filming was pretty much completed and I assembled the workprint

for Grant to see before he left the service to return home to Texas. For the remainder of the year, I edited the sound and

picture and scraped together the money to make a final release print. In December of 1985, I switched jobs to work as a civilian

employee at the 1369th Audiovisual Squadron (the new name for the old Photo Squadron).

|